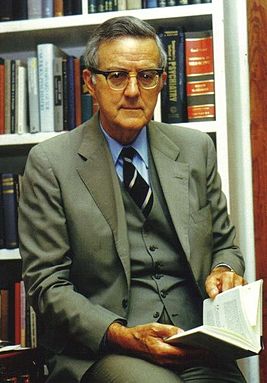

Ian Pretyman Stevenson (October 31, 1918 )

The life cycle 6 3

Important years of life

1920 3

1923 6

1929 3

1932 6

1938 3

1941 6

1947 3

1950 6

1956 3

1959 6 the first important independent year of life

1965 3

1968 6

1974 3

1977 6

1983 3

1986 6

1992 3

1995 6

2001 3

2004 6

February 8, 2007 = 2017

08.02.2007 >>> 2017.02.08 I think this is the date of his new birth … if, he wanted to live on Earth…this assumption I can not now prove 🙂

* continue the life cycle

2010 3

2013 6

2019 3

2022 6

2028 3

2031 6

2037 3

2040 6

2046 3

wiki information

Ian Pretyman Stevenson (October 31, 1918 – February 8, 2007) was a Canadian-born U.S. psychiatrist. He worked for the University of Virginia School of Medicine for fifty years, as chair of the department of psychiatry from 1957 to 1967, Carlson Professor of Psychiatry from 1967 to 2001, and Research Professor of Psychiatry from 2002 until his death

*Life cycles show the connection between people

*Critic Paul Edwards (1923–2004) was born and died in important years of life Ian Stevenson

Paul Edwards Born September 2, 1923 = 1934 = life cycle 124875 (3)

*We observe the invasion of the life cycle 124875 (3) – Paul Edwards into the life cycle 6 3 – Ian Stevenson

Critics, particularly the philosophers C.T.K. Chari (1909–1993) and Paul Edwards (1923–2004), raised a number of issues, including claims that the children or parents interviewed by Stevenson had deceived him, that he had asked them leading questions, that he had often worked through translators who believed what the interviewees were saying, and that his conclusions were undermined by confirmation bias, where cases not supportive of his hypothesis were not presented as counting against it.

…The philosopher Paul Edwards, editor-in-chief of Macmillan’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy, became Stevenson’s chief critic. From 1986 onwards, he devoted several articles to Stevenson’s work, and discussed Stevenson in his Reincarnation: A Critical Examination (1996). He argued that Stevenson’s views were “absurd nonsense” and that when examined in detail his case studies had “big holes” and “do not even begin to add up to a significant counterweight to the initial presumption against reincarnation.”Stevenson, Edwards wrote, “evidently lives in a cloud-cuckoo-land.”

Spouse(s) Octavia Reynolds (m. 1947)

He was married to Octavia Reynolds from 1947 until her death in 1983.

…After that, he held a fellowship in internal medicine at the Alton Ochsner Medical Foundation in New Orleans, became a Denis Fellow in Biochemistry at Tulane University School of Medicine (1946–1947), and a Commonwealth Fund Fellow in Medicine at Cornell University Medical College and New York Hospital (1947–1949).

(1959). “A Proposal for Studying Rapport which Increases Extrasensory Perception,” Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 53, pp. 66–68.

(1959). “The Uncomfortable Facts about Extrasensory Perception”, Harper’s, July.

*Chester Carlson (1906–1968), the inventor of xerography, offered further financial help. Tucker writes that this allowed Stevenson to step down as chair of the psychiatry department and set up a separate division within the department, which he called the Division of Personality Studies, later renamed the Division of Perceptual Studies. When Carlson died in 1968, he left $1,000,000 to the University of Virginia to continue Stevenson’s work. The bequest caused controversy within the university because of the nature of the research, but the donation was accepted, and Stevenson became the first Carlson Professor of Psychiatry

Books

(1974). Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation (second revised and enlarged edition). University of Virginia Press.

(1974). Xenoglossy: A Review and Report of A Case. University of Virginia Press.

In September 1977, the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease devoted most of one issue to Stevenson’s research. Writing in the journal, the psychiatrist Harold Lief described Stevenson as a methodical investigator and added, “Either he is making a colossal mistake, or he will be known (I have said as much to him) as ‘the Galileo of the 20th century’.” The issue proved popular: the journal’s editor, the psychiatrist Eugene Brody, said he had received 300–400 requests for reprints.

Despite this early interest, most scientists ignored Stevenson’s work. According to his New York Times obituary, his detractors saw him as “earnest, dogged but ultimately misguided, led astray by gullibility, wishful thinking and a tendency to see science where others saw superstition.” Critics suggested that the children or their parents had deceived him, that he was too willing to believe them, and that he had asked them leading questions. In addition, critics said, the results were subject to confirmation bias, in that cases not supportive of the hypothesis were not presented as counting against it. Leonard Angel, a philosopher of religion, told The New York Times that Stevenson did not follow proper standards. “[B]ut you do have to look carefully to see it; that’s why he’s been very persuasive to many people.”

Skeptics have written that Stevenson’s evidence was anecdotal and by applying Occam’s razor there are prosaic explanations for the cases without invoking the paranormal. Science writer Terence Hines has written: The major problem with Stevenson’s work is that the methods he used to investigate alleged cases of reincarnation are inadequate to rule out simple, imaginative storytelling on the part of the children claiming to be reincarnations of dead individuals. In the seemingly most impressive cases Stevenson (1975, 1977) has reported, the children claiming to be reincarnated knew friends and relatives of the dead individual. The children’s knowledge of facts about these individuals is, then, somewhat less than conclusive evidence for reincarnation.

…Stevenson described as the leitmotif of his career his interest in why one person would develop one disease, and another something different. He came to believe that neither environment nor heredity could account for certain fears, illnesses and special abilities, and that some form of personality or memory transfer might provide a third type of explanation. He acknowledged, however, the absence of evidence of a physical process by which a personality could survive death and transfer to another body, and he was careful not to commit himself fully to the position that reincarnation occurs.

That he did not fully commit himself to one position, see Almeder 1992, pp. 58–61. He argued only that his case studies could not, in his view, be explained by environment or heredity, and that “reincarnation is the best – even though not the only – explanation for the stronger cases we have investigated.” His position was not a religious one, but represented what Robert Almeder, professor emeritus of philosophy at Georgia State University, calls the minimalistic reincarnation hypothesis. Almeder states the hypothesis this way:

There is something essential to some human personalities … which we cannot plausibly construe solely in terms of either brain states, or properties of brain states … and, further, after biological death this non-reducible essential trait sometimes persists for some time, in some way, in some place, and for some reason or other, existing independently of the person’s former brain and body. Moreover, after some time, some of these irreducible essential traits of human personality, for some reason or other, and by some mechanism or other, come to reside in other human bodies either some time during the gestation period, at birth, or shortly after birth…

Champe Ransom, whom Stevenson hired as an assistant in the 1970s, wrote an unpublished report about Stevenson’s work, which Edwards cites in his Immortality (1992) and Reincarnation (1996). According to Ransom, Edwards wrote, Stevenson asked the children leading questions, filled in gaps in the narrative, did not spend enough time interviewing them, and left too long a period between the claimed recall and the interview; it was often years after the first mention of a recall that Stevenson learned about it. In only eleven of the 1,111 cases Ransom looked at had there been no contact between the families of the deceased and of the child before the interview; in addition, according to Ransom, seven of those eleven cases were seriously flawed. He also wrote that there were problems with the way Stevenson presented the cases, in that he would report his witnesses’ conclusions, rather than the data upon which the conclusions rested.

Weaknesses in cases would be reported in a separate part of his books, rather than during the discussion of the cases themselves. Ransom concluded that it all amounted to anecdotal evidence of the weakest kind.

In Death and Personal Survival (1992), Almeder holds that Ransom was false in stating that there were only 11 cases with no prior contact between the two families concerned.. According to Almeder there were 23 such cases…

Events continue to develop, even after the transition of a person to another world …. HE continues to live 🙂 EXAMPLE Alan Mathison Turing ( born 23 June 1912 …) life cycle 6 3

* continue the life cycle

*…In an article published on Scientific American’s website in 2013, favorably reviewing Stevenson’s work, Jesse Bering, a professor of science communication, wrote, “Towards the end of her own storied life, the physicist Doris Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf—whose groundbreaking theories on surface physics earned her the prestigious Heyn Medal from the German Society for Material Sciences, surmised that Stevenson’s work had established that ‘the statistical probability that reincarnation does in fact occur is so overwhelming …that cumulatively the evidence is not inferior to that for most if not all branches of science.’ ”

NEXT 2019 🙂

P.S.

3,1415926535…

Studying the number Pi, I collected information on the years that are included in the number series. This I extracted from Pi – 1907, 1909, 1927, 1931, 1932, 1938, 1949, 1953, 1957, 1959, 1960, 1964, 1971, 1989, 1995 2019 (

Igor Galyona ( life cycle 6 3 ) igorgalyona@gmail.com

Alien.com.ua ( All my photos ) My research 2008-2012 (Water)

124875369.com ( All people 124875 36 9 🙂 My research

On earth, there are only three types of people who live on cycles

124875 (1)(2)(3)

36

9

On cycles we count important years of human life